Page 115

GLIMPSES OF CHILD–LIFE AMONG THE OMAHA TRIBE OF INDIANS.

The Indian child is born in an atmosphere charged with the myths of his ancestors. The ceremonies connected with his infancy, his name, and, later on, his dress and games, are more or less emblematic of the visible forms of the powers which lie around man and beyond his volition. This early training makes easy the beliefs and practices of the adult, even to the extravagances indulged in by the so-called medicine-men.

The Omaha tribe is divided into ten gentes. Until within less than a score of years the various ceremonies pertaining to the different gentes were performed. Even now, when the people have left their villages and are scattered upon their individual farms, many of the customs which were purely social remain in force, and the distinctions of the gentes are still preserved. The tribe used to camp in a circle, and each gens had its permanent place. When moving out on the annual hunt, the opening of the circle was always in the direction in which the tribe was going. The five gentes which formed the northern or Instasunda half of the tribal circle were always in the same relative position to the northern end of the opening. The same was true of the southern or Hungacheynu half. It was as though the circle, with its opening, was laid over either to the east or the west, without disturbing the divisions. Therefore, although the tribe might camp in different localities, the unchanged relative position of each gens gave a fixity to the home of the child and determined his playmates, as boys of one side of the circle played against those of the other side.

Each gens had its mythical ancestor or patron, to whom all the names given to its members referred. The name was bestowed by the father or grandfather on the fourth day after birth. Sometimes the occasion was marked by a feast or some ceremony, such as painting the child in a symbolic manner. These observances, however, were frequently omitted.

When the child can walk steadily, about the third year, it is taken by the parents to the tent of an old man of the Instasunda gens, to have its hair cut for the first time, and moccasins put on its feet. Hitherto it had run about barefoot. When the child is presented, the old man gathers up the hair on the top of its head and binds it in a tuft, then severs it with a knife, and lays the bunch away in a pack. Then a new pair of moccasins are put on the child, and the old man lifts the little one by the arms and turns it round, following the sun, letting its feet touch the ground at the four points of

![]()

Page 116

the compass. When the east is reached, the child is urged forward, and bade to "walk forth on the path of life." Upon reaching home, the father of the child cuts its hair after the manner which symbolizes the mythical patron of the gens in which the child is born. This cutting of the hair in a symbolic style is repeated every year, after the first thunder, when the grass has begun to be green, until the child is about seven or eight years old. The boy is taken to the old man only once. The father always cuts the hair symbolically, as among the Omahas the child belongs to the gens of its father.

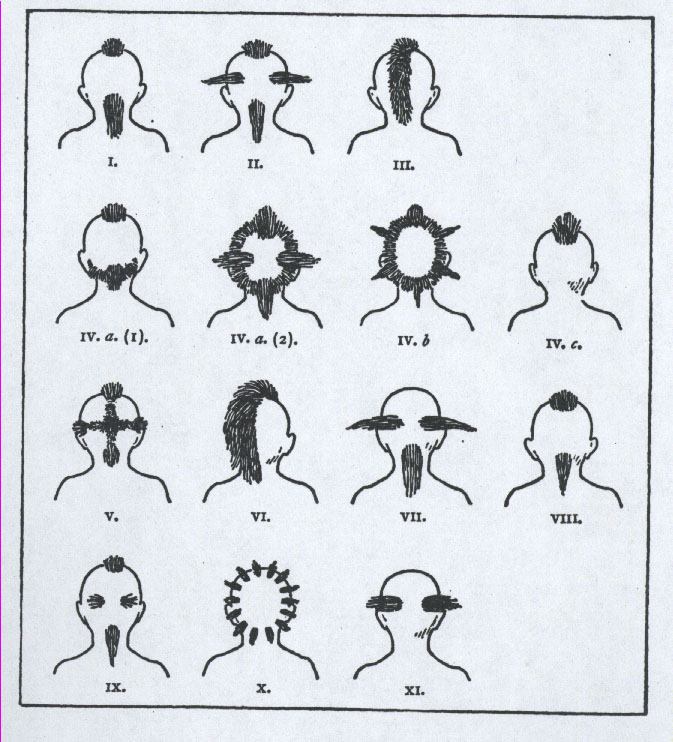

The following are the different modes of cutting the hair of Omaha children. Beginning with the Waejinste gens, situated at the southern end of the opening, we will take up the gentes in their consecutive order in passing around the tribal circle, until we reach the Instasundae gens, at the northern end of the opening.

I. Waejinste: Cut off all the child's hair from its head, leaving a tuft in front and a long lock behind; typical of the elk's head and tail.

II. Inkaesabbae: The head made bare, all but a front tuft, a short lock behind, and a lock on each side the crown; symbolizing the head, tail, and horns of the buffalo.

III. Hunga: The head shorn, all but a ridge of hair, about two inches wide, from the forehead to the neck; representing the back of the buffalo.

IV. Thatada: This gens is peculiar, as its subdivisions have different mythical patrons, and the child's hair is cut according to the sub-gens in which he is born. a. The Wazhingaetaze (bird subgens): Shear the head, leaving a fringe around the base of the skull, a short lock in front, and a broad lock behind. Sometimes, as among the Eagle people, broad locks are left on the sides. These represent the wings; the fringe, the body feathers; the other locks, the head and tail of the bird. b. The Kae-in (turtle sub-gens): Make the head bare, leaving a short lock at the front and nape of the neck, and two short locks on each side of the head; symbolizing the shell of the turtle, with his head, tail, and four legs visible. c. The Wasabbae etaze (black bear sub-gens) have the head bare, with a broad lock over the forehead, to indicate the bear's head.

V. Kan-ze: In cutting the hair, leave a tuft over the forehead, one at the neck, one on each side, and from each of these four tufts, representing the four points of the compass, a narrow line of hair runs up to a round tuft on the top of the head. This cut is emblematic of the four winds.

VI. Ma-thin-ka-ga-hae: Cut off the hair from one side of the head, and leave that on the other side long. This style is sometimes used by men who have had certain dreams or visions, but this is distinct in its significance from the manner of cutting the child's hair. This cut, for the child, typifies the wolf.

Page 117

VII. Tae-thin-dae: Make the head bare, with the exception of one long lock behind, and one short one on each side of the crown; indicating the buffalo horns and tail.

VIII. Ta-pa: All the hair is cut but a small bunch over the forehead and a long, thin lock behind; representing the head and tail of the deer.

IX. Ingrezhe-dae: Leave only a small lock in front, a similar one behind, and a tuft each side of the crown; representing the head and tail, and the knobs indicating the growing horns of the buffalo calf.

X. Instasunda: The head left entirely bare, or else a few thin and short locks around the bare head. The last symbolizes reptile teeth, the former the hairless body of snakes and creeping things. This is a thunder gens. In seven of the gentes there is a Ne-ne-ba-tan sub-gens. These

Page 118

refer to the duties connected with the tribal pipes. The children born in these subdivisions have their hair cut in the manner peculiar to this sub-gentes rather than in the style emblematic of the gens patron. The Ne-ne-ba-tan children (see IX. in the cut) have the head bare, except a lock each side of the crown; indicating horns.

During the most impressionable years the children are accustomed to look upon the queerly symbolic heads of their playmates, and they never forget in after life the picture their comrades presented, nor its significance.

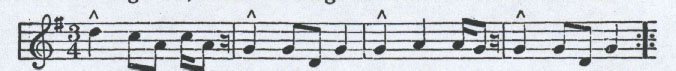

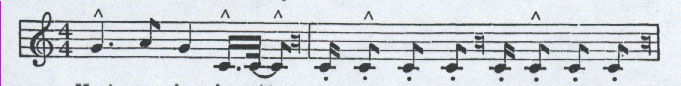

One of the favorite games of children from five to ten years of age is called "Ou-hae-ba-shun-shun," the crooked path. Fancy some ten or twenty youngsters, the boys under eight naked all but a string tied about their bulging little bodies, the girls in a short smock; the heads of the boys cropped after the manner of their birth gens, the breezes catching the odd locks, representing wings and tails, and waving them about. The leader, one of the older boys, sizes his crew, putting the smallest at the end of the Indian file. Each child grasps with its right hand the belt-cord of the one in front. At the word of the leader all start off at a shuffling trot, keeping time to the following tune, which all sing:—

Under no circumstances must one break from the line unless so ordered, and all must follow the leader and do exactly as he does. Off they go, bent on mischief, winding around trees, bushes, tufts of grass, through puddles, and among the tents. If an old woman chances to be pounding corn, the line circles about her, and each little left hand will seize some corn, until at last, with exhausted patience, she rises to chastise the imps. But they are too quick for her, having, at the word, scattered like partridges to cover. Should any one have hung his corn to dry on a frame low enough for this singing file of children to reach, each child will break off an ear, and the company make their way, singing and trotting on their crooked path, to some sheltered nook, where they halt, kindle a fire, roast the captured ears, and merrily eat the same.

There is a similar game, played by older boys, and even young men, called "Wa-tha-dae," —to call upon one. The leader of the game orders one of the party to go and do some deed, generally mischievous in character. Witnesses are sent to see that the act is committed. If the youth fails to accomplish the commission, he is dipped in a stream, or punished in some way. This game usually makes much sport for the youths and the elders of the tribe.

Page 119

Still another game of like nature is played, the "Ou-nae-the-ga-he," —to make a fireplace. The youths build a fire outside the camp, and the oldest becomes the leader. He takes a stick and thrusts it in the ground before one of the party, saying, "We will have so and so to eat." The one challenged takes up the stick, throws it back to the leader, and starts in search of the food. He is not always particular as to the manner of obtaining it. When the youth returns, he hands the article secured to the leader, who proceeds to cook it. . When all is ready, the company approach the leader, two by two, to receive their portion of the feast. The leader hands it over, crossing his arms so that the one opposite the leader's right hand gets the food held in the left, and the one opposite the left hand receives what the leader holds in his right. If any portion remains after all are served, there is a general scramble to get it away from the leader. The youth with the longest hair is placed at the end of the circle, and his companions wipe their greasy fingers on his locks!

There are many games played by children which mimic the occupations of mature life. Going on the hunt, with all the stir of preparation; taking down and putting up tents, the tall stalks of the sun-flower serving as poles; the attack of enemies; the meeting of friendly tribes and their entertainments, —all these furnish incidents for days and days of play. Deft-fingered children make toys out of clay, modelling men and animals, and also any articles they may have seen white people use, even to the fashioning of houses after those seen at the agency or mission.

There are silent games, as well as noisy ones. Two persons will sit and stare at one another, to see who will laugh first. Sometimes boys and girls play at the following game, which is called "Ke-tumbae-ah-ke-ke-tha," —contending with the eyes by looking.

A number of young folk may be together, when suddenly one of the number will call out, "Tha-ka!" whereupon all must repeat the word, beginning at one end of the circle round to the other. After this word is spoken silence must be maintained; no one must even smile. Whoever breaks the spell is punished. Water is poured over the offender, or his head snapped with fingers. Sometimes children play this game after they are put to bed, and many a sober face with dancing eyes peers over the covers, until sleep comes, and morning breaks the spell.

One might come upon a group of boys all intent in watching one of their number. He is holding a stick a foot or more long, one edge of which is full of little cuts. His right-hand forefinger touches every cut, beginning at the end held in his left hand, and with each touch of a cut he repeats "Duah." The game is to see which boy

![]()

Page 120

can touch the most cuts on the stick, and say "Duah" without taking a breath. It is a most absorbing game for the time being.

The songs sung by mothers to their children are generally the scraps that occur in myths. Story-telling is an important part of home life, and winter is the favored season; the children, however, carry the songs out among the summer blossoms, and the snakes do them no harm.

There is much of the picturesque in the old circular earth-lodge, with the fire burning brightly in the centre; the inner circle is made smaller by hanging skins or blankets between the row of posts, to shut out the chilling draught. The children sit on the hard ground about the fire, or on the ends of the long logs that feed the flames, unwilling to go to bed, and teasing for a story, a story, while the women clear away the remains of the evening meal, and the young mother dances her baby in her arms. Finally the grandfather yields to the children's importunities, and tells the following: —

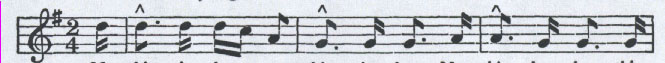

"Long ago the muskrat had a long, broad tail. It was very useful, and gave the muskrat much pleasure. The beavers, who had no tails at that time, used to watch the muskrat build dams and dwellings, and they were filled with envy. They saw how the muskrat enjoyed himself when he sat upon his tail and slid down the hills. So the beavers lay in wait for the muskrat. Suddenly they seized him. Some of the beavers took the muskrat by the head, while others caught hold of his tail and pulled. Finally the broad tail came out, and left the muskrat with only a thin little stem of a tail. The victorious beavers put on the broad tail, and were able to do all that the muskrat had done. The muskrat was desolate. He wandered over the country, wailing for the loss of his tail. The animals he met offered him such tails as they had, but he despised their offers, and gave them hard words in return. It was the gopher that sang this song, and all the other animals repeated it to the muskrat as he went about crying:"—

Back to reference

Back to reference

Back to reference

Page 121

(The meaning the words may be rendered: "Ground-tail, Ground-tail, you who dragged your tail over the ground; Ground-tail, Ground-tail!")

As the grandfather sings, slapping his thigh to keep the time, up jump the children and begin to dance, bending their knees and bringing down their brown feet with a thud on the ground. The baby crows and jumps, and the old man sings the song over and over again, until finally the dancers flag, and sleep comes easily to the tired children.

Among the stories told to children by their mother, or one of the older members of the family, the following is a favorite. The writer has heard it told many times, with much dramatic action. It relates to one of the characters under which the rabbit appears in the myths.

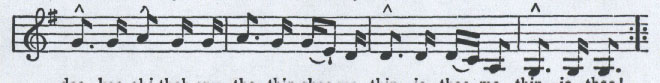

"Wa-han-the-she-gae (the orphan) lived with his grandmother. They were both very poor. One day he went out to dig roots. A flock of turkeys were also out walking. He was about to pass them, when one called out, 'There goes Wa-han-the-she-gae; let us call to him and ask him to sing for us, that we may dance.' Whereupon one of the turkeys hailed Wa-han-the-she-gae, and he advanced toward them. Then the spokesman turkey said, 'We have no one to sing for us, and we want to dance.' Wa-han-the-she-gae told the turkeys to stand two by two in a circle. He sat down at one side, placing near him the bag he had brought to carry the roots in. The turkeys made themselves ready; they crooked their necks, made their wattles red, drooped their wings, spread their feathers and tails, and moved their feet uneasily, in anticipation of the dance. Then said Wa-han-the-she-gae, 'You must all shut your eyes as you dance; for whichever one of you looks will always have red eyes!' So he began to sing, and the turkeys to dance."

(The words may be rendered: "He who looks will have red eyes; will have red eyes. Spread your tails; spread your tails!")

"Soon he called out, 'Tun-gae gan machey agaha egaha; tungaegan mashe agaha egaba!' (You who are larger dance outside; you who are larger dance outside!) The turkeys obeyed the order. As a fine,

![]()

Page 122

plump turkey passed him in the dance, he would seize it and thrust it in the bag, singing all the while, to keep the dance going. By and by one of the turkeys peeped a little bit, and saw Wa-han-the-she-gae in the act of bagging a turkey! He shouted, 'Wa-hoi! Na-thu-hakchee chey nu-ah-wa-the a-thae-ah-ka-ha!' (Wa-hoi! He has already nearly exterminated us!) Then all the turkeys opened their eyes and saw it was true, —but few were left! So they spread their wings and flew away over the trees, but their eyes became red as they flew. Wa-han-the-she-gae called out, as they rose in the air, 'You may go, but hereafter you shall be called "Zee-zee-ka!"' (the name for turkey). Then Wa-han-the-she-gae rose, shouldered his bag, and went home. Entering his tent, he tied the bag securely, laid it away, and called for his grandmother. Soon she came, and he said: 'Grandmother, you must not open this bag. I am going away for a little while, and you must let the bag alone.' He went out. While he was gone the grandmother became curious about the bag. She looked at it, then felt of it; it was full of lumps that kept moving. 'This is very queer,' she said, feeling it all over. 'I will just peep in; there will be no harm in that.' So she untied the string, and tried to hold it as she opened it a very, very little. All of a sudden the bag shook in her hands; there was a whirr, a dash of feathers over her face, and the tent was full of turkeys, flying through the opening and beating about, trying to get out. The old woman was frightened out of her wits. When she came to her senses, she slipped off her smock, and began running after the sole remaining gobbler, whipping him as she ran. At last she caught him, and put him back in the bag. Just then Wa-han-the-she-gae returned, and, seeing what had happened, began to scold, telling his grandmother she 'had no ears,' for he had told her not to open the bag. More words passed between them, and then he bade her go out-doors and sit with her head covered, for he was going to make a feast for some Pawnees. She went out, and did as she was bidden. Wa-han-the-she-gae cooked the turkey, and dished it in a wooden bowl. When this was done, he went quietly out of the tent, made a great rattling of buffalo-robes, and, lifting the tent-door flap and letting it drop with a loud noise, would call out, 'Now-ah! See-thae-muc-ca thae-sha-thu!' (Hail! Rabbit-chief!) He repeated these actions and greetings several times. And the old grandmother, sitting outside, said under her covers: 'Oh, my grandson! how well he is known by the great men of the Pawnees!' Then Wa-han-the-she-gae began to eat the turkey, keeping up the while a lively talk in Pawnee all by himself. He ate and ate, until nothing was left but the bones!"

Back to reference

Page 123

Many a group of children may be seen under the trees, in summer, playing "Im-bae the-an-jae." Putting their small robes or blankets about them, drawing the ends back with their arms, which they cross behind under the fall of the robe, spreading their hands and fingers beneath the robe, and flapping them, in imitation of the turkey's tails; then, hopping and jumping, they sing the song of Wa-han-the-she-gae, and dance the dance of the turkeys.

Back to reference

| More Omaha Heritage E-texts |