Page 215

THE OMAHA BUFFALO MEDICINE-MEN.

AN ACCOUNT OF THEIR METHOD OF PRACTICE.

Amoung the bluffs of the Missouri River valley, there stood an Indian village, the inhabitants of which were known as the Omahas. Although missionaries had been among these Indians, many were yet in their savage state. The traders, who were present long before the advent of the missionaries, taught the people nothing that would elevate them above their superstitions and strange beliefs; and the echoes of the Indians' religious and war songs still resounded through the hills, and in their ignorance they were happy.

In this village many of the days of my childhood were spent. By the lodge fire I have often sat, with other little boys, listening to the stories handed down by my forefathers, of their battles with the Sioux, the Cheyennes, and the Pawnees; to the strange tales told of the great "medicine-men," who were able to transform themselves into wild animals or birds, while attacking or fleeing from their enemies; of their power to take the lives of their foes by super-natural means; and of their ability to command even the thunder and lightning, and to bring down the rain from the sky. Like all other little savages of my age, I, too, loved to dream of the days when I should become a warrior, and be able to put to shame and to scalp the enemies of my people. But my story is to be about the buffalo medicine-men.

It was on a hot summer day that a group of boys were playing, by the brook which ran by this Omaha village, a game for which I can-not find an English name. I was invited to join them; so I took part in the gambling for feathers, necklaces of elk-teeth, beads, and other valueless articles which were the treasures of the Indian boy. In the village, preparations were going on for the annual summer hunt, and all the people were astir in various occupations. Here and there sat women in the shade of their tents or sod houses, chatting over their work. Warriors were busy making bows and arrows, shaping the arrowshafts, and gluing the feathers to them; while in the open spaces or streets a number of young men were at play gambling as we were, but using a different game. Now and then a noisy dispute arose over the game of the young men, but by the interference of the older men peace would be restored.

Towards the afternoon, our game grew to be quite interesting, there being but one more stake to win, and the fight over it became exciting, when suddenly we were startled by the loud report of a pistol. We dropped our sticks, scrambled up the bank of the brook,

![]()

Page 216

and in an instant were on the ridge, looking in the direction of the sound to see what it meant. It was only a few young men firing with a pistol at a mark on a tree, and some noisy little boys watching them. One of our party suggested going up there to see the shooting, but he was cried down, as he was on the losing side of our game, and accused of trying to find some excuse to break up the sport. We were soon busy again with our gambling, and points were made and won back again, when we heard three shots in succession: we were a little uneasy, although the shouts and laugh of the men, as they joked, quieted us, so that we went on with the game. Then came another single loud report, a piercing scream, and an awful cry of a man: "Hay-ee!" followed by the words, "Ka-gae ha, wanunka ahthae ha! O friends! I have committed murder!" We dropped our sticks, and stared at one another. A cold chill went through me, and I shivered with fright. Before I could recover myself, men and women were running about with wild shouts, and the whole village seemed to be rushing to the spot, while above all the noise could be heard the heartrending wail of the man who had accidentally shot a boy through the head. The excitement was intense. The relatives of the wounded boy were preparing to avenge his death, while those of the unfortunate man who had made the fatal shot stood ready to defend him. I made my way through the crowd, to see who it was that was killed. Peering over the shoulders of another boy, I saw on the ground a dirty-looking little form, and recognized it as one of my playmates. Blood was oozing from a wound in the back of his head, and from one just under the right eye, near the nose. The sight of blood sickened me, as it did the other boys, and I stepped back as quickly as I could.

A man just then ordered the women to stop wailing, and the people to stand back. Soon there was an opening in the crowd, and I saw a tall man come up the hill, wrapped in a buffalo robe, and pass through the opening to where the boy lay; he stooped over the child, felt of his wrists, then of his breast. "He is alive," the man said; "set up a tent, and take him in there." The little body was lifted in a robe, and carried by two men into a large tent which was hastily erected. A young man was sent in haste to call the buffalo medicine-men of another village (the Omahas lived in three villages, a few miles apart). It was not long before the medicine-men came galloping over the hills on their horses, one or two at a time, their long hair streaming over their naked backs. They dismounted before the tent, and went in one by one, where they joined the buffalo doctors of our village, who had already been called. A short consultation was held, and soon the sides of the tent were thrown open to let in the fresh air, and also that the people might witness the operation. Then began a scene rarely if ever witnessed by a white man.

Page 217

All the medicine-men sat around the boy, their eyes gleaming out of their wrinkled faces. The man who was first to try his charms and medicines on the patient began by telling in a loud voice how he became possessed of them; how in a vision he had seen the buffalo which had revealed to him the mysterious secrets of the medicine, and of the charm song he was taught to sing when using the medicine. At the end of every sentence of this narrative the boy's father thanked the doctor in terms of relationship. When he had recited his story from beginning to end, and had compounded the roots he had taken from his skin pouch, he started his song at the top of his voice, which the other doctors, twenty or thirty in number, picked up and sang in unison, with such volume that one would imagine it could have been heard many miles. In the midst of the chorus of voices rose the shrill sound of the bone whistle accompaniment, imitating the call of an eagle. After the doctor had started the song, he put the bits of root into his mouth, grinding them with his teeth, and, taking a mouthful of water, he slowly approached the boy, bellowing and pawing the earth, after the manner of an angry buffalo at bay. All eyes were upon him with an admiring gaze. When within a few feet of the boy's head, he paused for a moment, drew a long breath, and with a whizzing noise forced the water from his mouth into the wound. The boy spread out his hands, and winced as though he was again hit by a ball. The man uttered a series of short exclamations, "He! he! he!" to give an additional charm to the medicine. It was a successful operation, and the father, and the man who had wounded the boy, lifted their spread hands towards the doctor to signify their thanks. During this performance all of the medicine-men sang with energy the song which had been started by the operator. There were two women who sang, as they belonged to the corps of doctors.

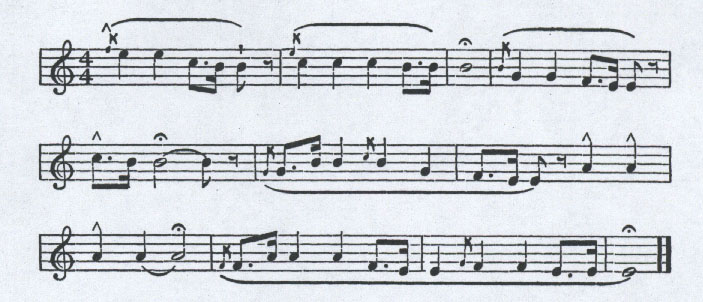

The following are two of the songs sung at this operation:—

Page 218

Thae'-thu-tun thae'-aw thae

Thae'-thu-tun thae'-aw thae

Thae'-thu-tun thae'-aw time

Tha'e-aw thae

Ae'-gun ne'-thun thae'-aw thae tae'-aw ma

Shun-aw-dun thae-aw thae

Ae'-gun thae'-thu-tun thae'-aw thae

Shun' thae-aw thae.

TRANSLATION.

From here do I send,

From here do I send,

From here do I send,

I send.

Thus, the water to send, I'm enjoined,

Therefore do I send,

Thus, from here do I send,

Therefore do I send

The first four lines of this song can be readily understood, but the last four need an explanation. The meaning is, Because I am commanded, or instructed (by the buffalo vision), to send the water (the medicine) from this distance, therefore I do so. or.

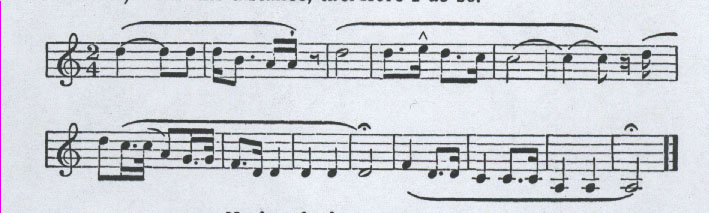

Ne-thun tha-dae-aw ma,

Ne-thun tha-dae-aw mae,

Ou-hae ke-thae e-thae-aw mae tho hae,

Ne-thun tha-dae e-thae-aw mae tho hae.

Page 219

TRANSLATION.

The pool of water, they proclaim,

The pool of water, they proclaim,

Yield to his entreaties, they declare they will,

The pool of water, they proclaim, sending their voices to me.

The composer of this song is said to have seen in a vision a number of buffalo attending one of their number who was wounded. The vision was given to the man to reveal to him the secret of a healing potion. The first two lines mean that the attending buffalo, the doctors, have indicated a pool of water in a buffalo wallow as the place where the wounded one shall be treated; the third line, that they assent to the entreaties of the injured animal to be taken to the water, that his wounds may be healed in it. In the fourth line the word "ethae" has a different meaning than in the third line, and is not quite the same pronunciation. In the fourth line the word signifies to send in this way or in this direction. As all the words that the visionary animals uttered were directed to the dreamer's ears, the last line of the song is intended to convey this meaning. The round pool of water they proclaim sending this way; that is, their voices to me.

This song is quite poetical to the Indian mind. It not only conveys a picture of the prairie, the round wallow with its gleaming water, and the buffalo drama, but it reveals the expectancy of the dreamer, and the bestowing of the power of the vision upon him for the benefit of sufferers.

Although there were twenty or thirty doctors in attendance, only four of them operated upon the patient in the manner above described. In a severe case like this one, all of the medicine-men unite in consultation, and each man is entitled to his share of the fees. When the case is not so severe, the relatives of the patient select one or two of the doctors to attend the wounded person. The buffalo doctors are organized into a society, and treat nothing but wounds. It is seldom that they lose a patient, but, when called to a person in a critical condition, they declare the hopelessness of the

Back to reference

![]()

Page 220

case, so that no blame may be attached to them should the sufferer die. All night the doctors stayed with the patient, the four men taking turns in applying their medicines, and dressing the wound.

The next morning the United States Indian agent came into the village, driving a handsome horse, and riding in his shining buggy. He first went to the chief, and demanded that the wounded boy be turned over to him. He was told that none but the parents of the child could be consulted in the matter; and if he wanted the boy, he had better see the father. The agent was said to be a good man, and before he offered his services to the government as Indian agent he had studied medicine, so that he could be physician to the Indians as well as their agent. I had attended the mission school for a while, and learned to speak a little of the white man's language; and as the government interpreter was not within reach, the agent took me to the parents of the boy, who were by the bedside of their sick one. On our way to the place we heard the singing and the noises of the medicine-men, and the agent shook his head, sighed, and made some queer little noises with his tongue, which I thought to be expressive of his feelings. When our approach was noticed, every one became silent; not a word was uttered as we entered the tent, where room had already been made for us to sit, and we were silently motioned to the place. We sat down on the ground by the side of the patient, and the agent began to feel of the pulse of the boy. The head medicine-man, who sat folded up in his robe, scowled and said to me, "Tell him not to touch the boy." The agent respected the request, and said that unless the boy was turned over to him, and was properly treated, death was certain. He urged that a sick person must be kept very quiet, and free from any kind of excitement, for that would weaken him, and lessen the chances of recovery. All this I interpreted in my best Omaha, and the men listened with respectful silence. When I had finished, the leader said, "Tell him that he may ask the father of the boy if he would give up the youth to be cared for by the white medicine-man." The question was asked, and a deliberate "No" was the answer. Then the medicine-man said, "He may ask the boy if he would prefer to be doctored by the white man." While I was translating this to the agent, the boy's father whispered in his child's ear. I then interpreted the agent's question to the boy. He held out his hand to me, and said with an effort, "Who is this?" He was told that it was "Sassoo," one of his friends. I held his hand, and repeated the question to him, and he said, "My friend, I do not wish to be doctored by the white man." The agent rose, got into his buggy, and drove off, declaring that the boy's death was certain, and indeed it seemed so. The boy's head was swollen to nearly twice its natural

![]()

Page 221

size, and looked like a great blue ball; the hollows of his eyes were covered up, so that he could not see, and it made me shudder to look at him.

Four days the boy was treated in this strange manner. On the evening of the third day the doctors said that he was out of danger, and that in the morning he would be made to rise to meet the rising sun and to greet the return of life.

I went to bed early, so that I could be up in time to see the great ceremony. In the morning I was awakened by the singing, and approached the tent, where already a great crowd had assembled, for the people had come from the other villages to witness the scene of recovery. There was a mist in the air, as the medicine-men had foretold there would be; but as the dawn grew brighter and brighter, the fog slowly disappeared, as if to unveil the great red sun that was just visible over the horizon. Slowly it grew larger and larger, while the boy was gently lifted by two strong men, and when up on his feet, he was told to take four steps toward the east. The medicine-men sang with a good will the mystery song appropriate to the occasion, as the boy attempted this feeble walk. The two men by his side began to count, as the lad moved eastward, "Win (one), numba (two), thab'thin (three): "slower grew the steps; it did not seem as if he would be able to take the fourth; slowly the boy dragged his foot, and made the last step; as he set his foot down, the men cried, "duba" (four), and it was done. Then was sung the song of triumph, and thus ended the first medicine incantation I witnessed among the Omahas.

Before the buffalo medicine-men disbanded, they entered a sweat lodge and took a bath, after which the fees were distributed. These consisted of horses, robes, blankets, bears' claw necklaces, eagle feathers, beaded leggings, and many other articles much valued by Indians. The friends of the unfortunate man who shot the boy had given nearly half of what they possessed, and the great medicine-men went away rejoicing. One or two, however, remained for a time with the boy, and in about thirty days he was up again, shooting sticks, and ready to go and witness another pistol practice.

It is only recently that I have been able, through inquiry, to find out two of the most important roots used in the healing of wounds, but how they are used is known only to the medicine-men. And to obtain that knowledge one would have to go through various forms of initiation, each degree requiring expensive fees. One of these medicines is the root of the hop vine, humulus lupulus, and the other the root of the Physalis viscora.

Francis La Flesche.

| More Omaha Heritage E-texts |